Editor’s note: To read this blog post, “Amazon Conservation Team ayuda al censo de pueblos indígenas con capacidades Maxar” in Spanish, please click here.

In Santa Marta, Colombia, earlier this year, preparations began for a series of expeditions into the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. More than a dozen teams—each composed of indigenous peoples and western professionals—prepared their gear for weeks-long trips into the remote mountains. Giant bags of food supplies were piled high, filling an entire garage to the ceiling, ready to be hauled onto 4x4 trucks.

Why such an immense undertaking? It was time for the 2020 census of the Kogui-Malayo-Arhuaco (KMA) Indigenous Reserve. Like in the United States—where there is also a 2020 census underway—socio-economic information gathered during the census will have important ramifications for local communities. In Colombia, surveys provided to the National Lands Agency serve as the basis to strengthen indigenous land rights through the creation and expansion of indigenous reserves, a communal land designation that protects indigenous territories in perpetuity.

It is essential to ensure the utmost quality of socio-economic and geospatial data collected during the census surveys. In Colombia, rural land tenure is a highly contentious issue, especially within the context of the tenuous peace process signed in 2016. To ensure the legalization of indigenous territories, and to avert any potential conflicts with neighboring landholders, all details provided to the National Lands Agency must be precise. The census will play a vital role in the proposed 2020 KMA reserve expansion, the latest step in the historic process of territorial reclamation.

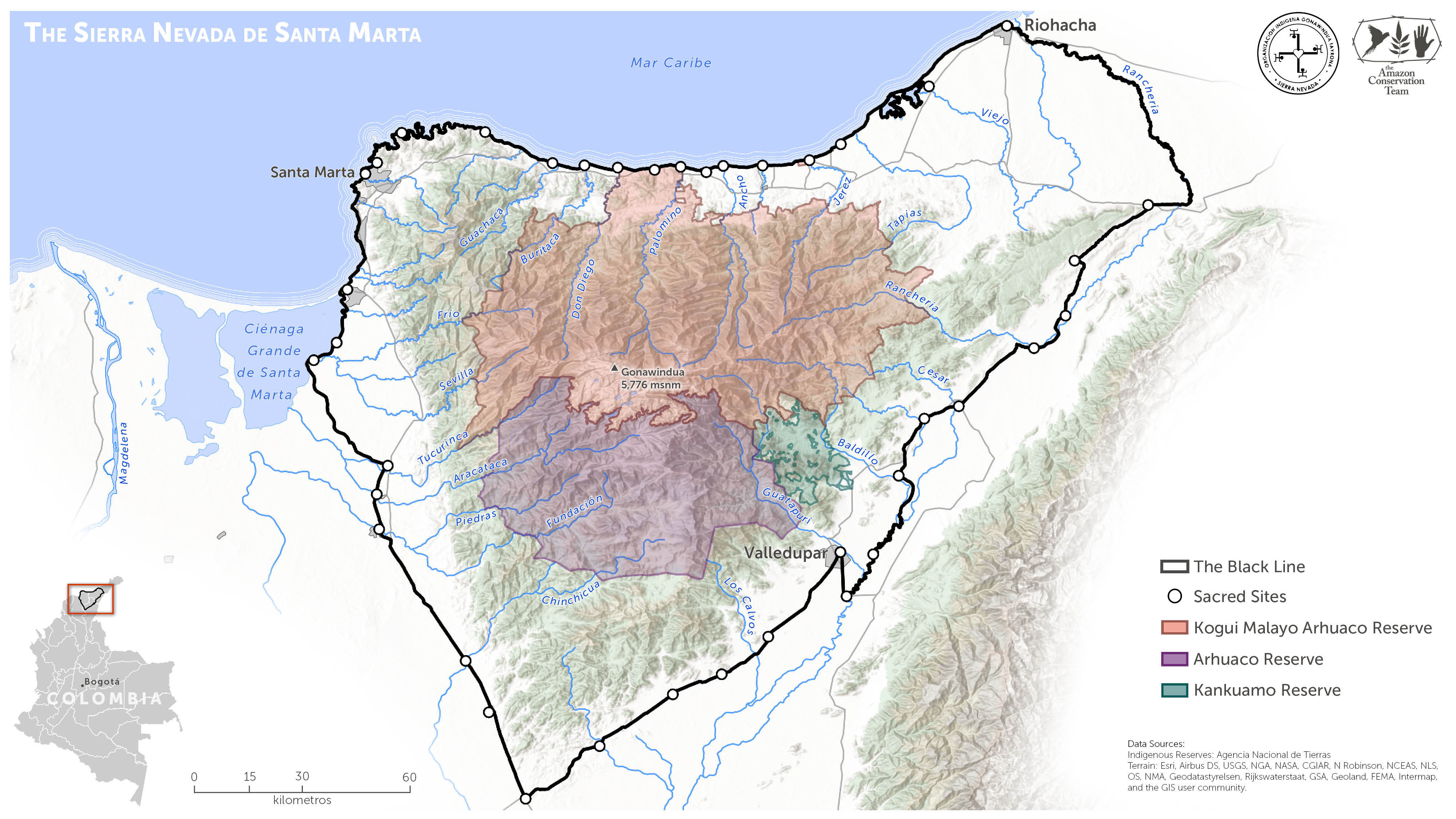

Conducting surveys across a vast and rugged mountain landscape presents a formidable challenge. Rising out of the Caribbean Sea, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta encompasses more than 10,000 square miles (17,000 km²). The snowcapped peaks of the Sierra reach heights of 18,700 feet (5,700 m). A dozen major rivers radiate from the central peak, carving deep ravines that make crossing from one valley to the next a daunting task.

The Sierra Nevada is home to the Kogui, Arhuaco, Kankuamo and Wiwa indigenous groups, whose collective ancestral territory is marked by a ring of sacred sites at the base of the Sierra known as the ‘Línea Negra’ (Black Line). Modern indigenous reserves cover just a fraction of their ancestral territories, and the Kogui have been working for generations to reoccupy their lost territories in lower elevations to reverse centuries of unwanted colonization and environmental devastation.

The Kogui association Organizacion Gonawindúa Tayrona (OGT) and the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) led the census coordination efforts, which included convening teams of young indigenous leaders, community organizers and mamos (traditional authorities) for planning and training exercises.

When the census expedition teams left Santa Marta before dawn, they followed paved roads along the coast where vast expanses of banana plantations have replaced native forests. Turning off the main road, the 4x4s climbed precipitous dirt roads leading to small frontier towns, where the census teams unloaded supplies and hauled them onto teams of mules. From there, they embarked on foot, following dusty trails through cattle ranches and coffee farms. Reaching steep inclines, they climbed switchbacks through increasingly large forest patches, passing scattered indigenous households until reaching high mountain passes with spectacular vistas, like the Surivaka pass in the photograph below.

After many difficult hours of hiking, the census teams arrived at their destinations: Kogui villages with densely clustered adobe houses crowned with conical thatched roofs adorned with broken clay pots. These towns, like Bunkuangueka in the photograph below, remain empty for most of the year. The entire village only gathers on the solstices and other special occasions for nights of ceremonial prayer, dancing and song within the immense ceremonial structures standing prominently in the center of each town.

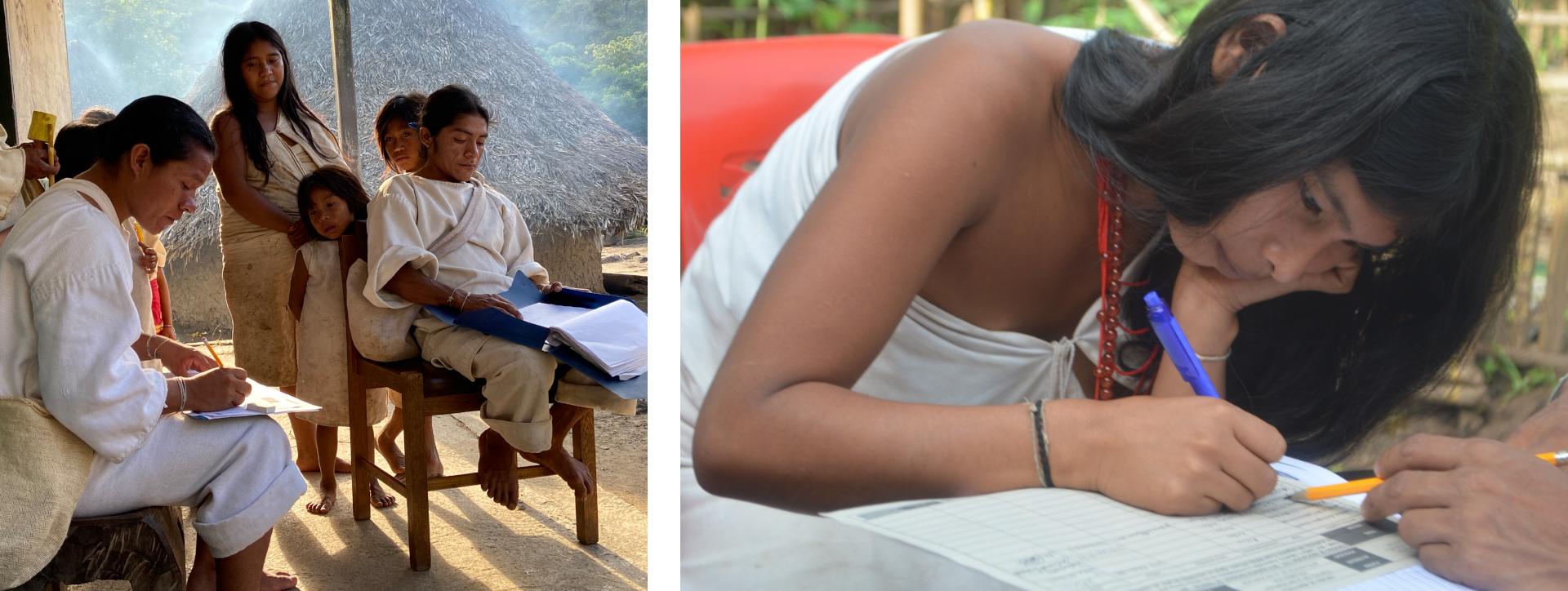

The census teams set up interview stations and met with each community member, as shown below. They responded to a series of questions from the official census form, including the names of family members living in their household, annual income, the number of cows and chickens they own and the types of produce grown in their garden. These interviews happened entirely in native languages and the Kogui left an ink fingerprint as a signature at the end of the survey.

Through these activities, Kogui youth facilitators emerged into new leadership roles in their communities, while receiving valuable experience in community organizing and data collection and tabulation. Many are the first in their families to graduate from western schools, and they talk eagerly of helping their communities protect their culture and territories by pursuing careers as teachers, lawyers or geographic surveyors.

Many Kogui youths participating in the census are part of OGT’s territorial team, a group focused on collecting land tenure information. Through a partnership with the Amazon Conservation Team over the past several years, OGT has learned how to use new mapping technologies, including GIS software, GPS units, smartphones equipped with data collection apps and Maxar’s high-resolution satellite imagery to locate and map priority properties. Throughout the census process, the census team georeferenced each town visited, providing a valuable geospatial component to socio-economic data so that OGT can better understand local dynamics in their territories.

As census activities concluded, community members gathered around a massive stone located just outside of town that defines a sacred site. Here, Mamo Rafael of Surivaka reflected on the importance of the survey:

“This census is to support us with the territory. To expand our territory, so that we can recover the sacred sites that are being destroyed ... We, the People of the Origin, have been fulfilling what was left to us, to protect our mother earth and also the order it has given us. For this, we have always been ready to protect the earth, so that it can be energized, so that it can also protect us, because these main sacred sites are always waiting to protect us human beings and also the animals.”

Upon returning to Santa Marta, the census teams tabulated and organized all of the data collected into immense spreadsheets while downloading and reviewing geospatial information in mapping software. They used Maxar’s high-resolution satellite imagery to verify village locations and to count the number of houses. Satellite imagery also revealed settlements not visited in the trip, enabling OGT to create the most comprehensive map yet of Kogui settlements. The combined socio-economic and geospatial data will be submitted to the Colombian government for inclusion in the national census as well as part of the application to expand the KMA reserve.

For indigenous communities, collective ownership of their lands is essential to their health and wellbeing. Without secure access to healthy forests, traditional indigenous cultural systems inevitably deteriorate and communities suffer. Healthy forests on indigenous lands provide a variety of ecosystem services that benefit thousands of people, including those living far outside of the indigenous territories. Forests regulate climate and water cycles, ensuring a supply of clean drinking water to urban centers miles away. Indigenous-managed forests provide valuable carbon sequestration and are essential for climate change mitigation. Notably, indigenous reserves are inexpensive to establish and monitor when compared to other land designations and carbon capture strategies, making indigenous land titling a cost-effective strategy for national governments to employ toward achieving their greenhouse gas emission reduction commitments.

The indigenous reserve land designation in Colombia also provides economic benefits to resident communities through property tax relief as well as access to government funding that enables communities to improve their quality of life and better manage their lands. The socio-economic and geospatial data collected during the 2020 KMA Indigenous Reserve census will provide irrefutable evidence of where these people live and help them obtain official ownership of their ancestral lands.

Brian Hettler, a geographer and cartographer with the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), works with indigenous communities in South America on participatory mapping initiatives that support indigenous land rights and rainforest conservation.

Maxar empowers non-profit organizations that uniquely benefit from the company’s geospatial data and analytics to advance their global development efforts. These Purpose Partners, including Amazon Conservation Team, reflect Maxar’s purpose, For a Better World. These organizations receive donations of imagery, analytics and service.