Outside of technical circles, the most well-understood measuring stick for the utility of satellite imagery is resolution. It’s a metric kind of like home runs in baseball—it tells you a lot about a player’s value, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. A player who can hit 30 home runs in a season can probably make a major league roster—but is such a player worth signing to a 10-year mega-deal to build franchise around? That depends on other factors, like their on-base percentage, age and durability, are they a liability in the field, etc.

Resolution is no vanity metric. Many missions—particularly national security missions—require imagery with enough detail to characterize activities on the ground with high confidence. It’s rarely good enough to know something is there or something is happening if you can’t tell what it is. Since Maxar launched the world’s first 30 cm commercial imaging satellite in 2014, this has become the gold standard for resolution that most customers have desired.

Rocket Lab Electron Rocket before launch at LC-1 in Mahia, New Zealand on November 20, 2020.

Beyond resolution, there are a host of other technical characteristics that ultimately relate to speed of access—how quickly can I get the image that I need? Yesterday, we got a great look at Rocket Lab’s Electron launch vehicle about four hours before it carried 30 satellites into orbit. Our WorldView-3 satellite was not passing directly over the New Zealand launch site; it was more than 440 miles to the east, requiring us to tilt the satellite 47 degrees from nadir (straight down) to get the shot. The target was more than 200 miles farther away than if it were directly beneath the satellite, and yet, due to WorldView-3’s large optical telescope, the resulting image still has 48 cm resolution—and we were able to collect it because of the satellite’s ability to point rapidly in any direction to take a shot, what we refer to as the satellite’s “agility,” combined with its ability to still collect good resolution at a distance, which we refer to as its “access.”

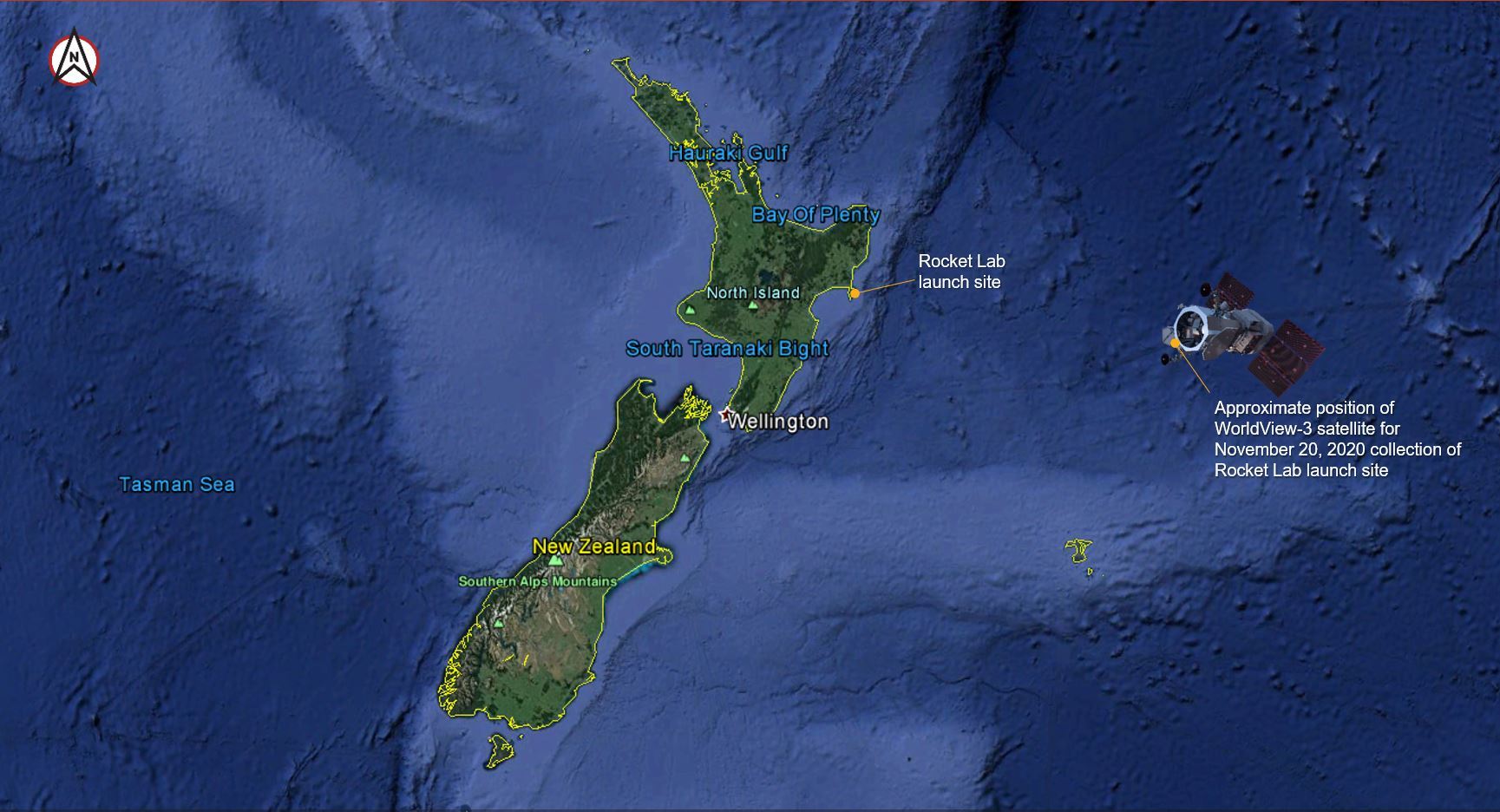

WorldView-3 location of high off-nadir collection of the Rocket Lab launch site in Mahia, New Zealand on November 20, 2020.

This image was actually not that difficult to collect. The whole world knew exactly where the rocket would launch from and when, so we had plenty of time to factor that into our collection plans. It gets harder and more complex when we have less information about where or when a certain activity will take place. Hypothetically, intelligence agencies might suspect that a rogue nation is planning to test a new missile sometime in the next few weeks. If that missile happens to be on a mobile launcher, it could be just about anywhere. That’s when the real value of agility comes into play. On timelines of 20 minutes or less, we can re-task our constellation based on the most current information. Maxar’s ability to collect large areas in a single overhead pass (think all of Belgium) also factors into a scenario like this, because you may only have a general idea of where to look. Those terabytes of imagery can be downlinked, processed, and securely distributed minutes after they have been collected. Then we can apply AI and ML tools to narrow the search space and find the needles in the haystack in time to affect the mission. And when we launch our WorldView Legion satellites next year, everything gets faster and better.

Pretty amazing stuff, right? While I wish I could say it was easy, these things are only made possible by the large infrastructure investments we’ve made, our deep commitment to innovation and the trusted partnerships with our customers we have forged over many years. Maxar has built the team to win championships.