In today’s world, with growing threats from nations with rapidly advancing technologies, we increasingly hear senior leaders in the Defense Department calling for revamping the antiquated way the U.S. government acquires new capabilities by leveraging commercial innovation and “buying commercial.” It’s important to understand what this actually means. Just because a U.S. government agency buys a product or service from a vendor does not mean it is “buying commercial.” When the Navy buys its warships from General Dynamics, that’s classic defense procurement—not buying commercial.

So what does it mean for the U.S. government to “buy commercial,” and when, where and why does this benefit government, and ultimately taxpayers and citizens?

At its heart, for the U.S. government to buy truly commercial products or services from a provider, two criteria must be met. First, the U.S. government can’t be the only customer of the provider; rather, the provider must have a substantial non-U.S. government business. Second, the provider must substantially invest its own capital, using its own (commercial) processes to develop the products and services it provides. The government can buy commercial under a range of business models, including the highly transactional (“swipe to buy”), long-term contracts or volume buys and even co-investment—whatever best meets the government’s needs. As long as the company is substantially serving customers beyond the U.S. Government and investing its own capital, then it’s commercial.

Buying commercial offers substantial and measurable advantages to the government. It spreads the cost of product development and operations across a larger customer base, so the U.S. government doesn’t foot the entire bill. It leverages commercial innovation, which is unshackled from antiquated procurement practices. And because of this, the government benefits from either declining cost or increasing value over time as those innovations are introduced into the market.

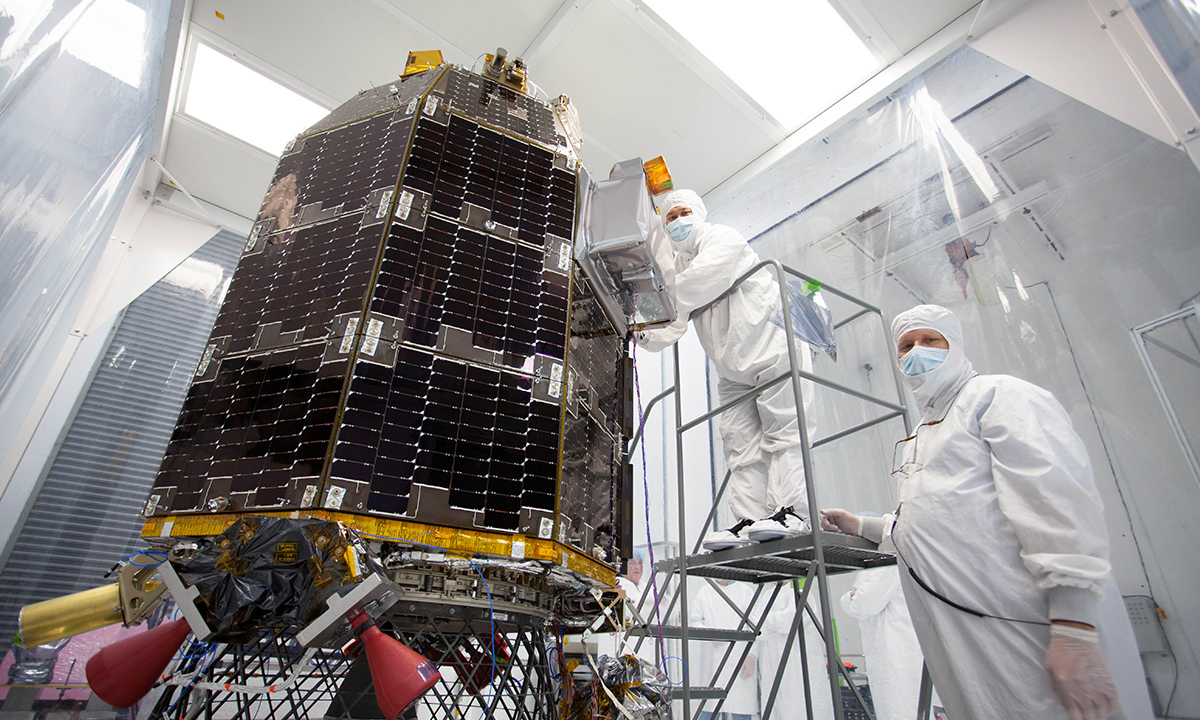

To see what this looks like in practice, let’s consider two examples. Maxar Technologies’ SSL developed the propulsion system for NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere Dust and Environment Explorer (LADEE) mission that studied the moon’s exosphere in 2014. The LADEE propulsion system was based on a standard system that has been proven on more than 100 commercial missions. It was essentially the same propulsion system—built in the same factory, by the same engineers, with the same tools—that is used on the SSL 1300 satellite platform that delivers television, radio and broadband internet for millions of commercial customers.

In the imagery part of the business, DigitalGlobe supplies the U.S. government with the vast majority of the commercial satellite imagery that supports mapping, disaster response, mission planning and situational awareness. This imagery is provided as a service, using the same satellites, ground infrastructure and expertise that are used to deliver imagery to commercial customers like Google, Facebook and The Gates Foundation. In all cases, both government and commercial customers benefit from greater value and more rapid innovation, since DigitalGlobe’s costs are shared more widely, and capabilities developed for one customer set can be leveraged by the other.

It's not uncommon for industries that began under U.S. government sponsorship to evolve into vibrant commercial industries, which enable the government to enjoy the benefits of buying commercial—once the government realizes that this shift has occurred and changes its buying behavior accordingly. Microelectronics began under U.S. government sponsorship of the ballistic missile program during the Cold War. They now power everything from our cars to our coffee makers, continue to improve according to Moore’s Law and are nearly entirely commercially funded. Space launch, which again began under U.S. government sponsorship, has in the past few years crossed over to being commercial; SpaceX was founded with private capital, offers launches for a fraction of the price of the traditional defense contractors and serves a balanced mix of commercial and government customers. And commercial Earth observation, which had been a secretive government monopoly until 1992, is today a business that serves a balanced mix of U.S. government and non-U.S. government customers, leveraging several billion dollars of commercial investment. In each case, now the U.S. government buys commercial and enjoys the benefits.

These transitions to buying commercial do not go unopposed. When the U.S. government is first to enter a new arena where there are no commercial sources, the responsible agencies must build up infrastructure and muscle memory to do the job themselves, or manage traditional defense procurements. This creates institutional inertia, and it’s human nature to resist change and offer arguments as to why this particular job can’t be performed by a commercial firm: it’s too critical; no firm could do it as well as the government (with its many years of experience); the government can’t depend on a firm that might go bankrupt; no commercial firm could possibly meet the government’s demanding requirements; and “our procurement rules don’t allow it.” We even see government regulation used as a tool to hold back commercial innovation. It’s important for senior leaders in government to recognize this pattern of excuses for what it is and to lead their organizations through the necessary changes.

Governments shouldn’t prevent private industry from commercializing a technology unless there are truly compelling reasons to do so, and they should buy commercial products and services that meet their needs without deluding themselves that traditional defense procurement is “buying commercial.” Following these principles will help to ensure the government gets the best possible value for its investments, and that taxpayers and society in general benefit from government investments to the greatest possible degree.